Square numbers proof

I recently signed up for the MFPL PhD Selection where we got some scientific tasks to solve. One involved proving some statement about square numbers right or wrong.

Question

Is any of the integer numbers, A, consisting of exactly 15 ones and 15 zeros a square-number, that is an integer B exists, such that B*B=A? The number A should always have 30 digits and also numbers with leading zeros are considered. Please explain your answer. A simple YES or NO is not sufficient.

Probing the statement approach

I’m definitely no Maths genius, so the first thing I would do was to basically build randomly some numbers with 15 1s and 15 0s and calculate their square roots to get a feeling.

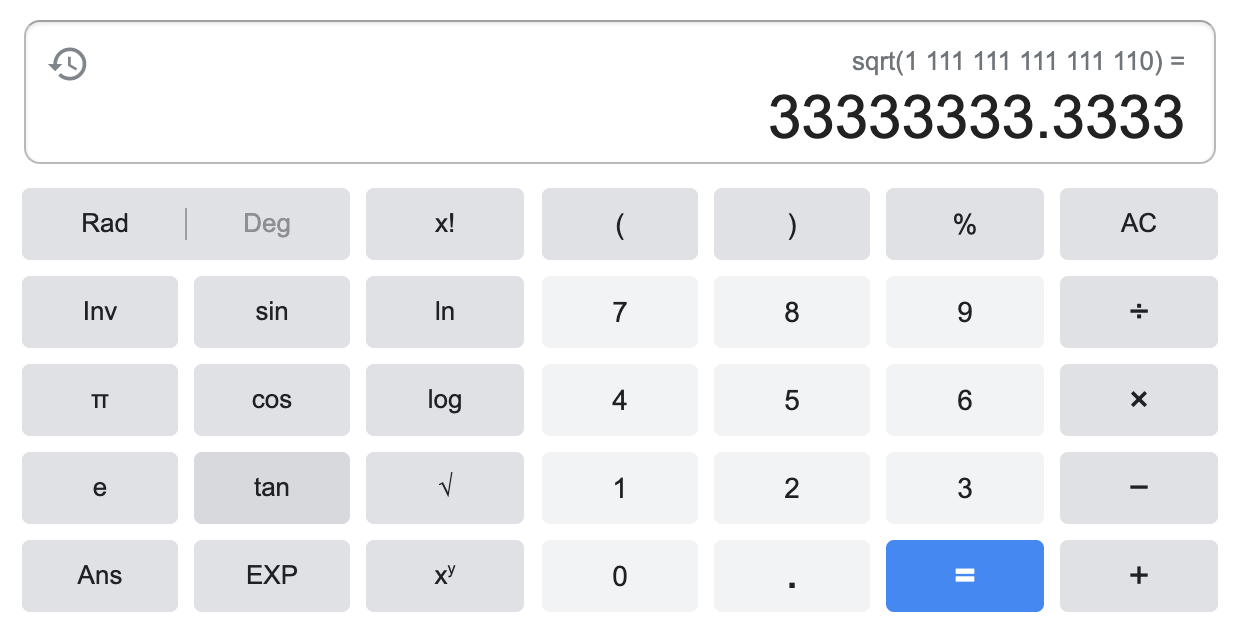

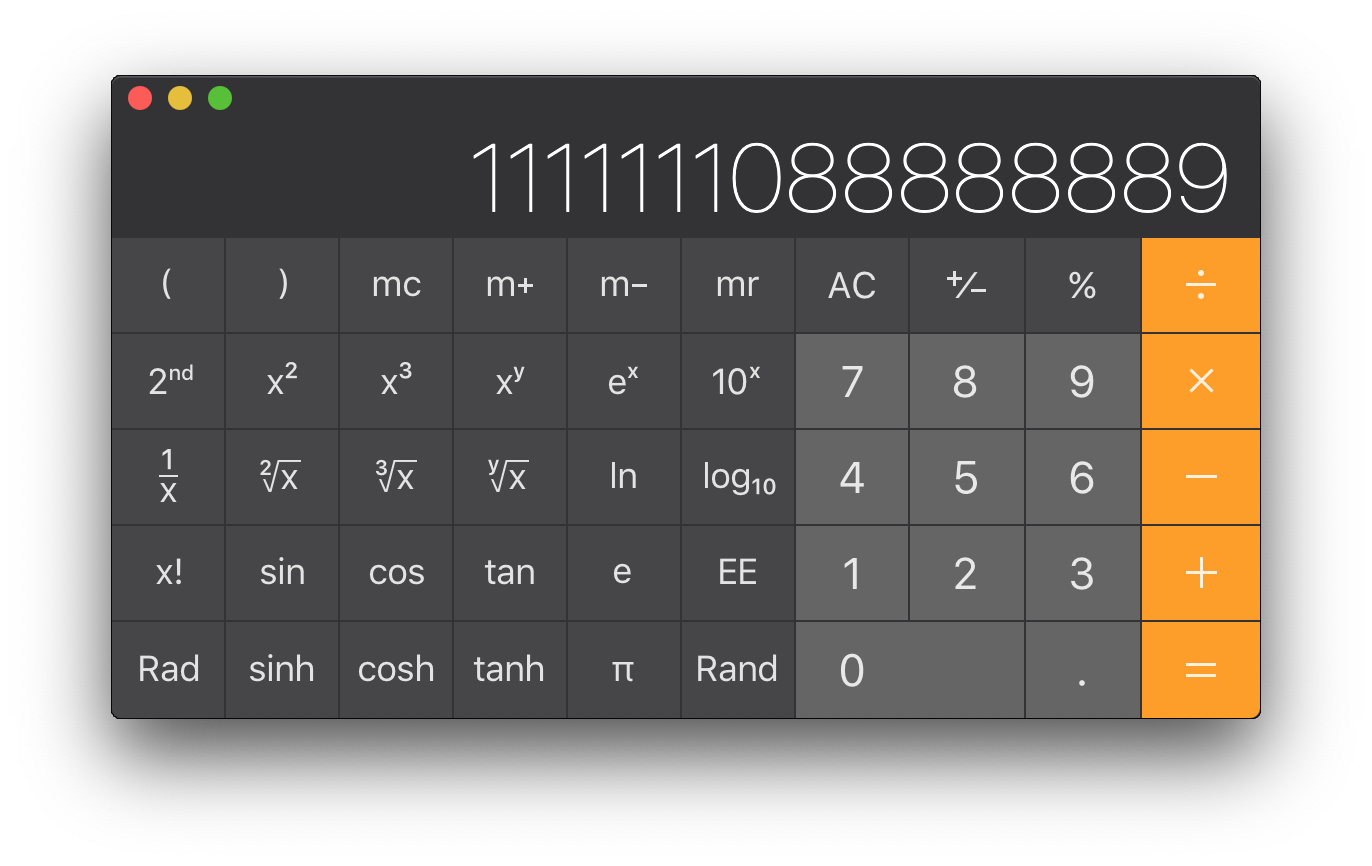

Here already I stumbled upon some misleading results since for bigger numbers as any number involving minimum 15 digits, the Apple calculator, R and Google tend to round and switch to scientific notation, making you believe you are looking at square numbers.

> a = 000000000000001111111111111110

> a

[1] 1.111111e+15

> sqrt(a)

[1] 33333333

> 33333333*33333333

[1] 1.111111e+15

As you can see, both R and Google calculator would make you believe \(33333333^2\) yields \(1111111111111110\) when in fact it does not - cross-checked with Apple calculator.

So now that I had after some detour already pretty quickly found an example proving the statement above wrong - which by the way already itself is sufficient to disprove the initial statement - but I wanted a little more sophistication.

I decided to take a rather lazy approach of reading up on properties of square numbers on Wikipedia and see whether any of them proves to be an easy no go. I came across the following:

- No square number ends in 2, 3, 7 or 8.

- The number of zeros at the end of a perfect square is always even.

- Squares of even numbers are always even numbers and square of odd numbers are always odd.

- The Square of a natural number other than one is either a multiple of 3 or exceeds a multiple of 3 by 1.

- The Square of a natural number other than one is either a multiple of 4 or exceeds a multiple of 4 by 1.

- The unit’s digit of the square of a natural number is the unit’s digit of the square of the digit at unit’s place of the given natural number.

- There are \(n\) natural numbers \(p\) and \(q\) such that \(p^2 = 2q^2\).

- For every natural number \(n\), \((n + 1)^2 - n^2 = (n + 1) + n\).

- For any natural number \(m\) greater than 1, \((2m, m^2 - 1, m^2 + 1)\) is a Pythagorean triplet.

So let’s just quickly go through them:

Property 1 does not really help because we can only construct numbers ending at 0 and 1, both apparently valid digits for square numbers.

Property 2 - we already hit the jackpot. Since we can freely distribute 0s in our numbers, it is trivial to create one with an odd number of zeros at the end.

Allrighty, let’s formalize it.

Proof: Square numbers ending in zeros strictly end with an even number of zeros

Theorem: Square numbers ending in zeros strictly end with an even number of zeros.

(1) Let \(k\) be an integer \(k \in \mathbb{Z}\) with \(k \geq 0\).

(2) Let \(n\) be any number ending in \(0\): \(n = (10k + 0)\).

(3) The perfect square of \(n\) equals to \(n^2 = (10k + 0)^2 = 100k^2\)

From (3) directly follows that any square number with ending zeros, strictly ends with zeros of a multiple of 2 - therefore an even number - of zeros.

We have proofed the theorem and therefore can use it to probe for counter-examples given the properties in our initial question.

Disprove statement by counterexample

It is trivial to find a number \(m\) with an odd number of ending zeros and 15 additional 1s.

Simplest example:

\[m = 1111111111111110\] \[\sqrt{m} = \sqrt{1111111111111110} = 33333333.33333331\dot 6\]Therefore it follows, that the question

Is any of the integer numbers, A, consisting of exactly 15 ones and 15 zeros a square-number, that is an integer B exists, such that B*B=A?

can be answered with No:

Not any integer number A, consisting of exactly 15 ones and 15 zeros is a square-number, that is an integer B exists, such that B*B=A.